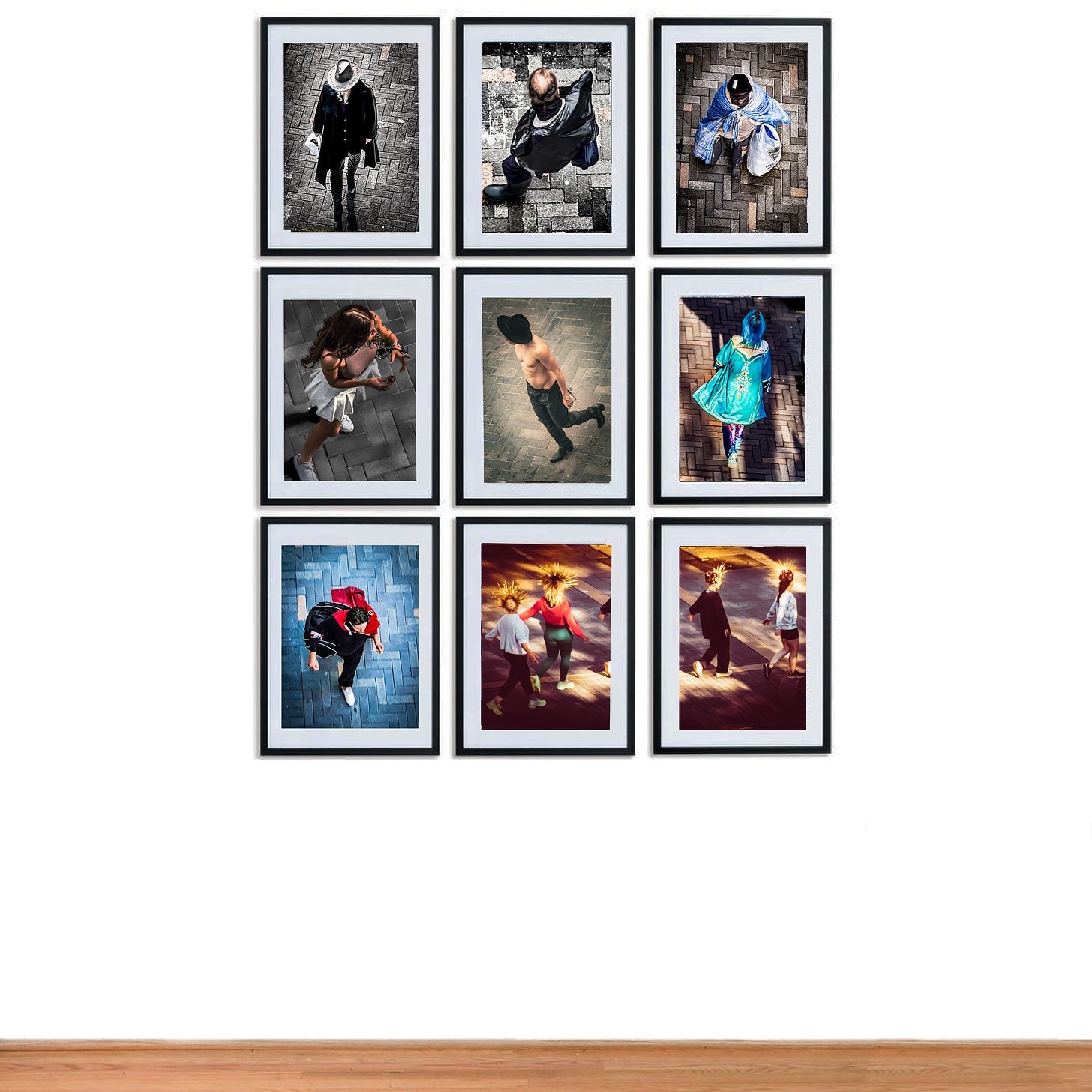

Like CCTV cams, drone footage, or crane shots, the photos are all taken from above, a fair distance from the subjects. This echoes the social distancing experienced over the pandemic, six-feet apart in-person and thousands of miles apart via virtual meetings. (The images are not to be emotionally distanced though — the point of each photograph was to imagine, with great empathy, what the story was for each “hero” in the frame, which also informed the aesthetic look). The photos also resonate with the state of surveillance we all now live in, the Camopticon, or the Panoptiphone, cameras everywhere, smartphones in every hand, recording and tracking everything, overtly and covertly.

What is a private moment in this milieu? Is there such a thing? Is privacy now simply being oblivious to observation? If so, then sleeping has to be the ultimate state of unawareness. It’s something one usually does privately, but here it was in a public setting, the man sleeping mid-day on the stairs.

Because of the self-imposed parameters of the photographic project (images of the street taken from a window above) there is no interaction with the subjects. They are unaware of the camera, and so are not performing in anyway. People in the wild. (Me, an urban Jane Goodall). Because I wanted natural behaviour, I made a point of never calling out to anyone below — though sometimes it was very tempting to ask them to walk by again because I’d missed a great photo — or even waving to them in the rare times they looked directly at the camera. The truth is in the unstaged, unguarded moment.

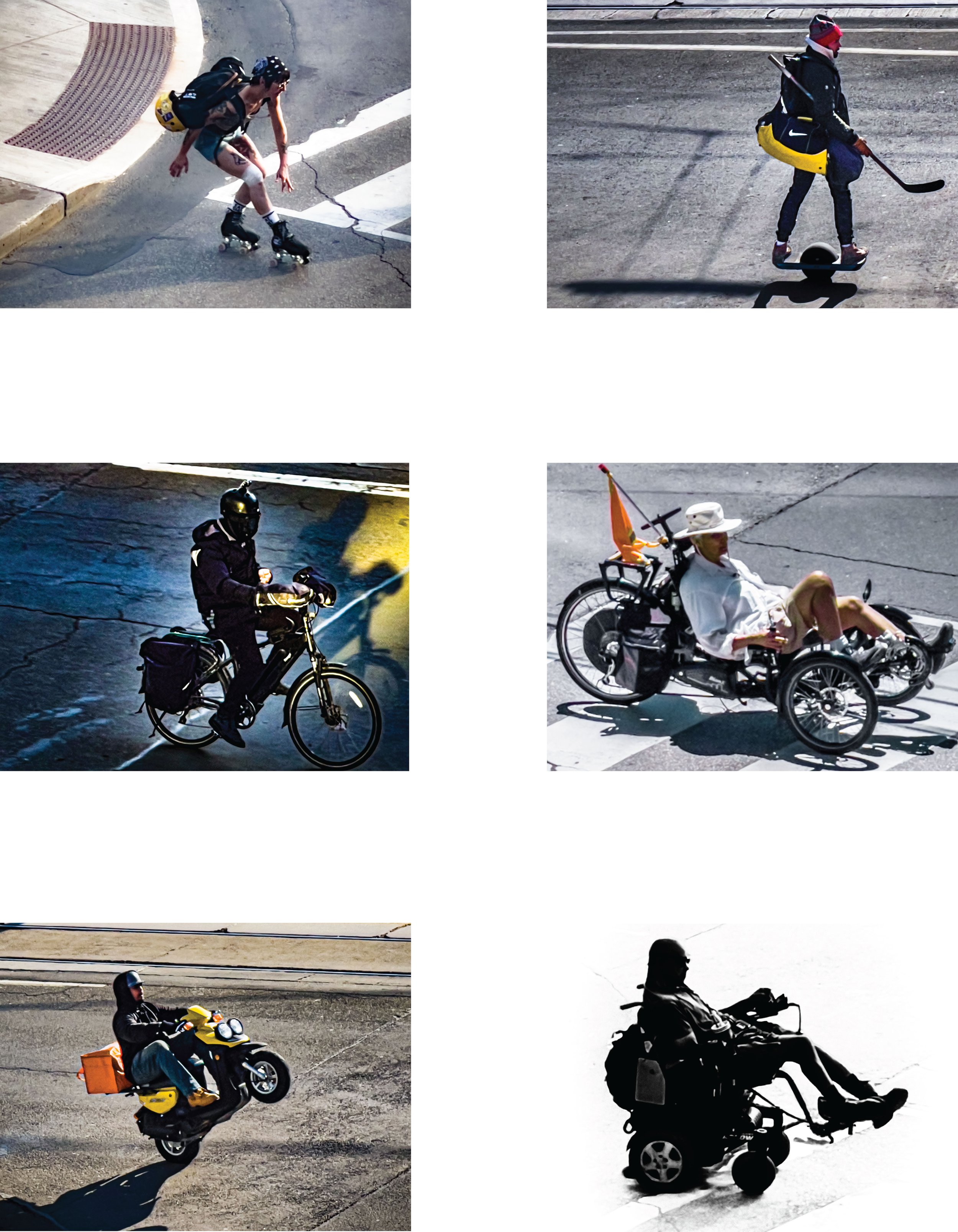

For the above image though, I broke the rules. I first noticed the man because of his funky hat and rolly suitcase, so I photographed him as he walked around. He’d pause and walk, pause and walk. He peed behind a dumpster, then stood in the side alley for a very long time, just looking at the street. Finally he went to the stairs, laid down his head, and fell asleep. It was now twilight. An hour or so later I looked out the window again. He was gone, but his luggage was still there. Half an hour later, it was still there. I was now worried for him. Those frequent pauses. So I went down to retrieve the rolly before someone took it. the rolly before someone took it.

All his ID — passport, healthcard, etc — was in the bag, so I tried to track him down via social media by his name, and a little sentence on a notepad he’d written, “Memoirs of a Wandering Bishop”. I sent messages to what may have been him and a relative. No response.

I kept looking out the window to see if he’d returned. By midnight I gave up. The next day I called the police; they said to turn the luggage in at the precinct. They’d keep it for 90 days and if it wasn’t claimed, burn it. There was a tag on his luggage, so I called the airline, explained the situation and left my number. About an hour later I got a call from across the country — his mother. She said he’d arrived in the city after a very long journey from the US by bus, and couldn’t get on the flight she’d booked him, and that he’d been exhausted. She’d managed to book him a hotel room early that morning.

I called the hotel and told him I had his luggage and where to come to get it. He’d come the next day. He didn’t have a phone, so I had to watch out for him. The next morning, about 20 minutes after the arranged time, I saw him on the sidewalk in front of a nearby restaurant, motionless. People were moving around him. He wasn’t looking around for an address. He just seemed… on pause.

Eventually he unfroze and came close enough so that I could shout to him and wave to him to wait. I brought his luggage down. I asked him about how he’d forgotten his bags. He said he was really tired after the long bus trip and was kinda just out of it.

He was soft spoken, and very grateful that someone had saved his luggage and ID. I told him to pass it along. He said he had been, for a long while, and that this was the first time someone had done it for him.

I asked him how he was going to get the rest of the way across the country since he couldn’t take a plane or train. Buses didn’t have routes that way anymore. I said maybe he could get a ride with a trucker. He’d been a trucker once, so that’s what he was going to try. I said there were people looking out for him, his family, even strangers like me.

We shook hands and I watched him go. He paused for awhile before turning the corner. I wasn’t sure if he knew how to get back to his hotel, about a 30 minute walk away. Or if he’d be able to get back to his family, who was thousands of miles away. Or if he’d be able to get back to, furthest away of all, himself.